14 Combined Loads

This chapter uses all the previously discussed concepts to determine the total normal stress and the total shear stress for a body subjected to various types of loading simultaneously. Axial forces (Chapter 5), bending moments (Chapter 9), and pressure (Chapter 13) may be applied in various combinations to give total normal stress. Transverse loads (Chapter 10) in multiple directions and torsion (Chapter 6) can combine to give total shear stress.

Understanding which loads lead to which types of stresses and in which directions requires having a good grasp of coordinate axes. In particular being able to distinguish between the longitudinal axis and the cross-sectional axes is important. This can change from body to body as different coordinate axes are used, but it can also change within an individual body according to changes in geometry. Section 14.1 reviews how to distinguish between the coordinate axes as well as defines generic terms that will allow us to express equations in a more generalized manner.

Section 14.2 reviews and expands on the various sources of normal stress. These normal stresses will be reframed in terms of the general axes discussed in @sect-14.1 so as to clarify which other normal stresses they may combine with. Section 14.2.1 revisits bending stress to express the unsymmetric bending stress equation in terms of general cross-sectional axes. Section 14.2.3 considers eccentric loading, which is a specific instance of combined normal stress in which normal forces result in bending.

Section 14.3 focuses on combining the various sources of shear stress to determine the total shear stress. To expand on the concepts discussed and used in Chapter 6 and Chapter 10, here we perform calculations based on both possible transverse loading directions as well as torsion. As in Section 14.2, this is accomplished using a general set of coordinate axes.

Section 14.4 further expands the above cases to situations in which all combinations of loading are possible and the general stress state is determined.

Note that determining internal reactions for the general problems presented in this chapter requires the use of 3D equilibrium equations, particularly for determining bending moments and torsion. You may thus find it helpful to review Section 1.4 to understand these calculations.

14.1 Coordinate Axes and Directions

Click to expand

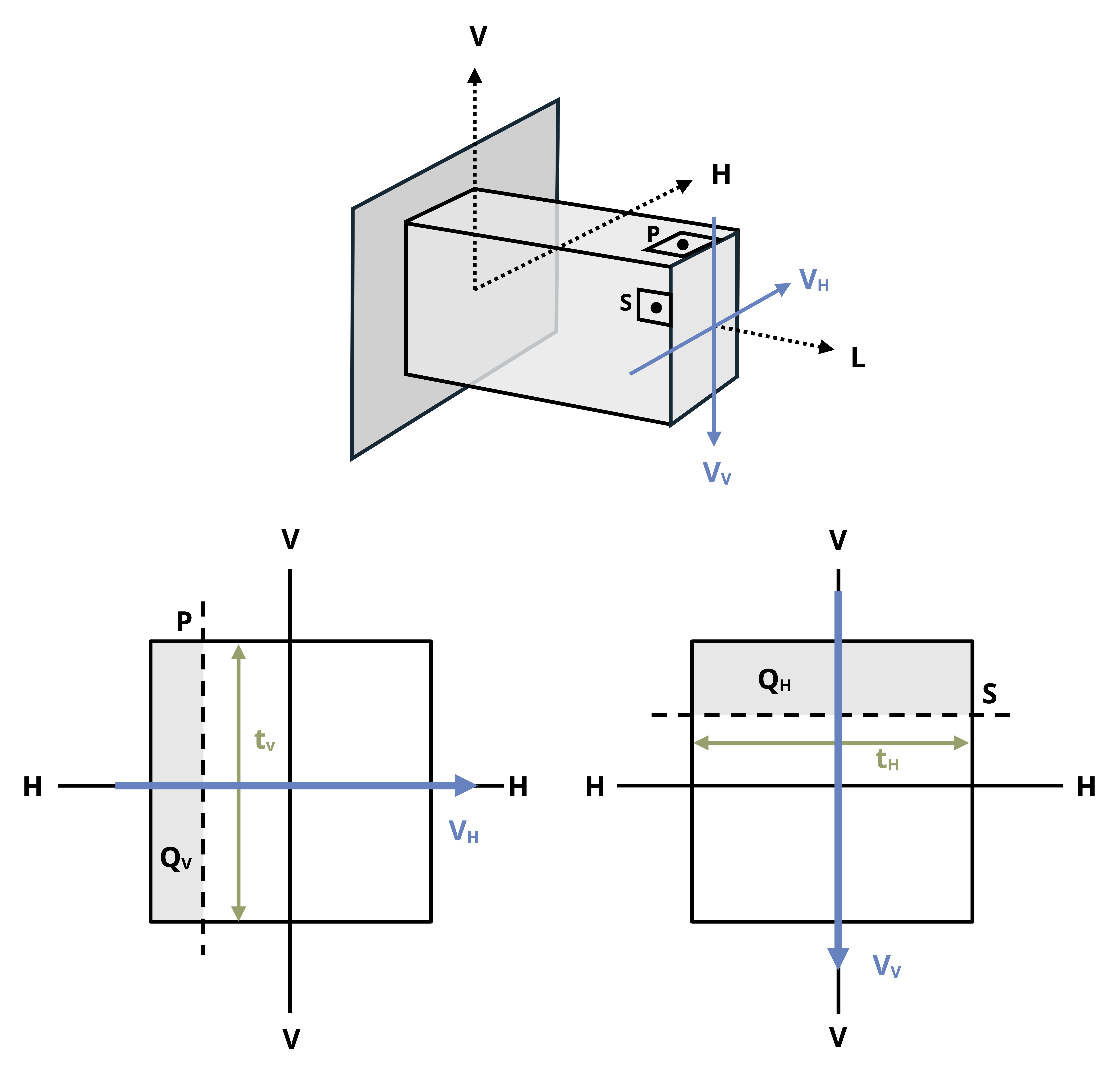

To generalize the discussion for any set of coordinate axes, we will use generic terms for the various directions, as shown in Figure 14.1. The vertical axis of the cross-section will be referred to as the V axis, the horizontal axis of the cross-section will be referred to as the H axis, and the longitudinal (axial) direction will be referred to as the L axis.

The longitudinal direction, synonymous with axial direction, is the direction perpendicular to a cross-section that is cut at a point of interest on a body. The cross-sectional axes are the axes drawn on the cross-section based on viewing the cross-section down the longitudinal axis.

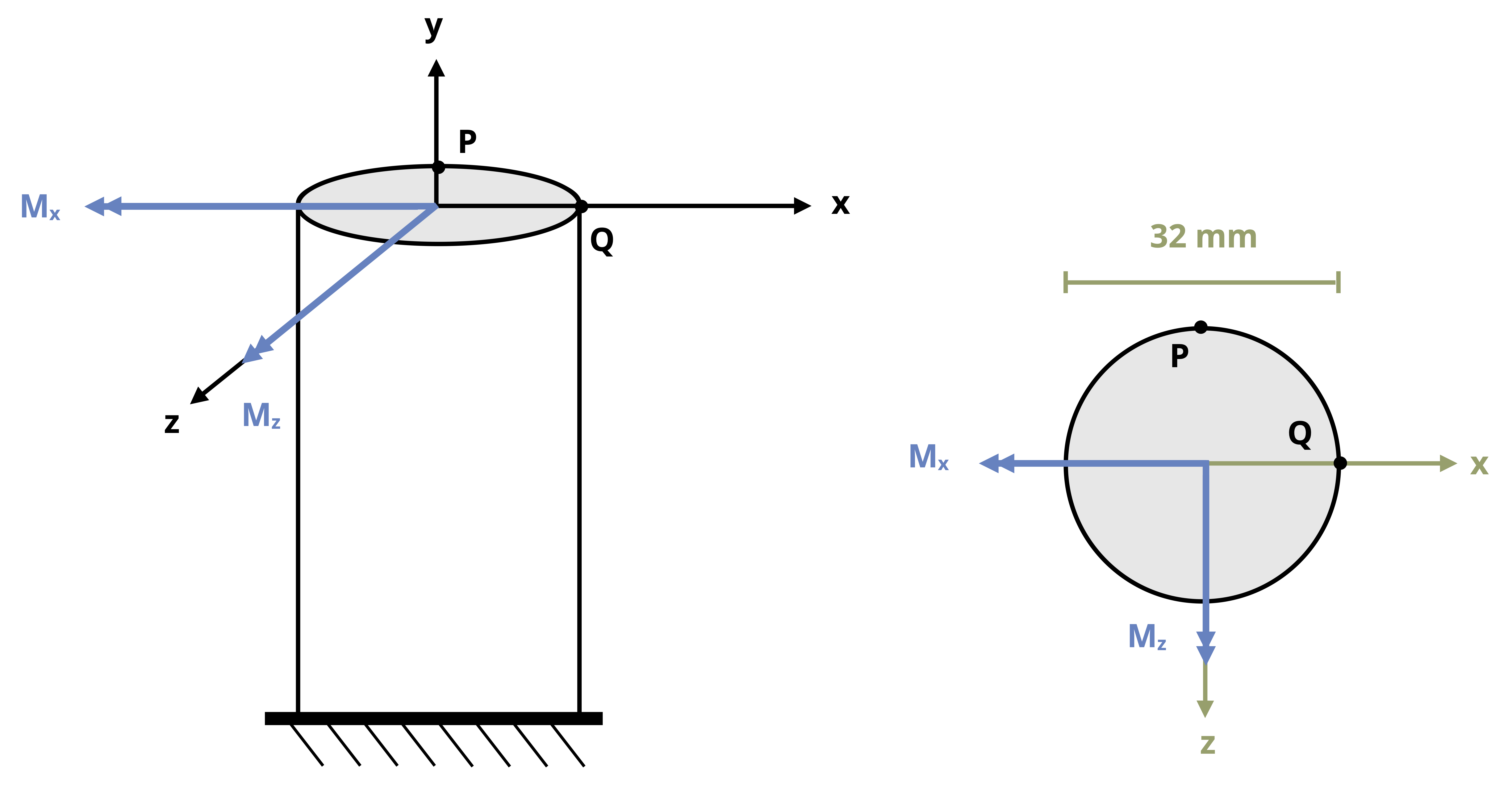

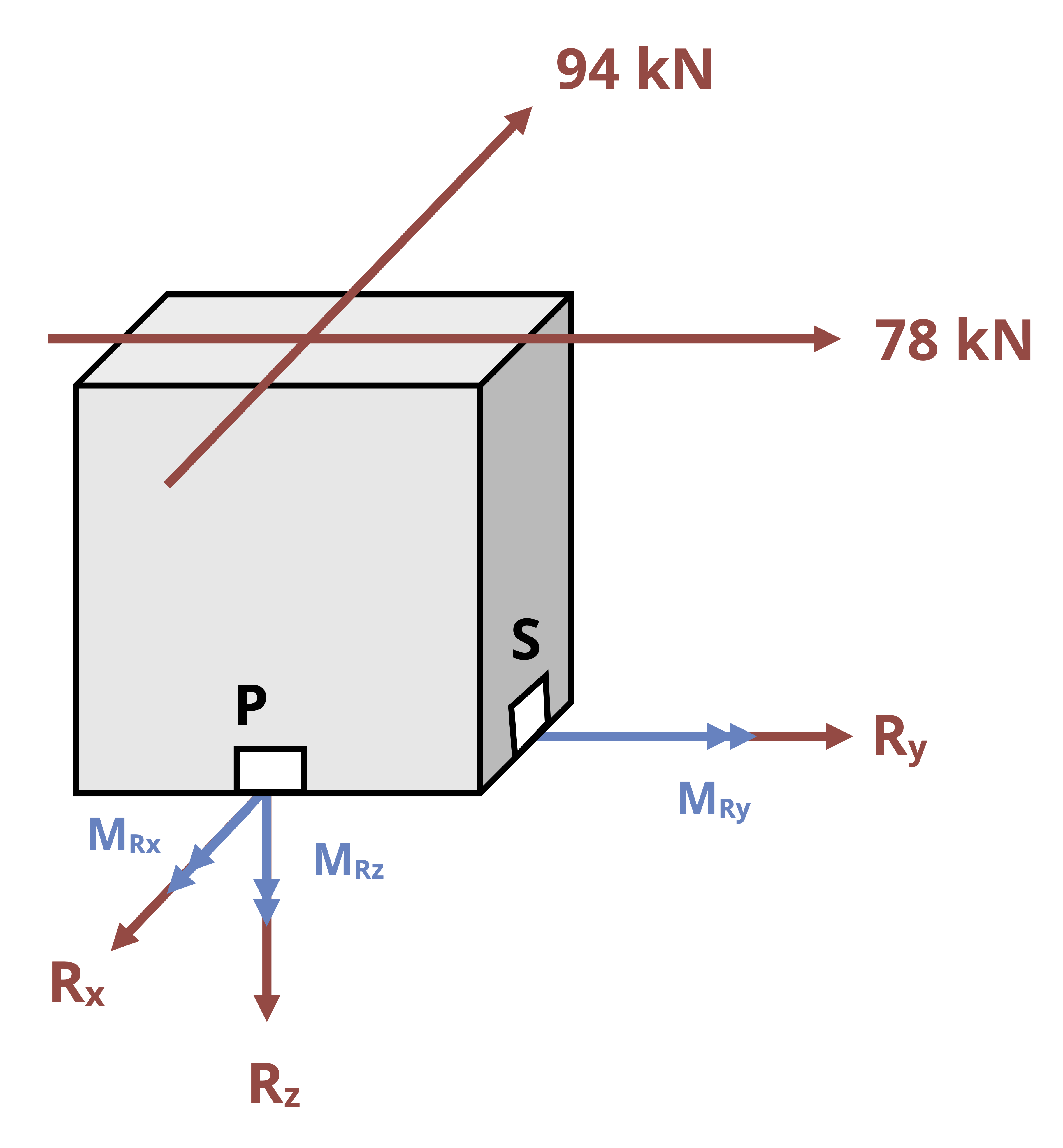

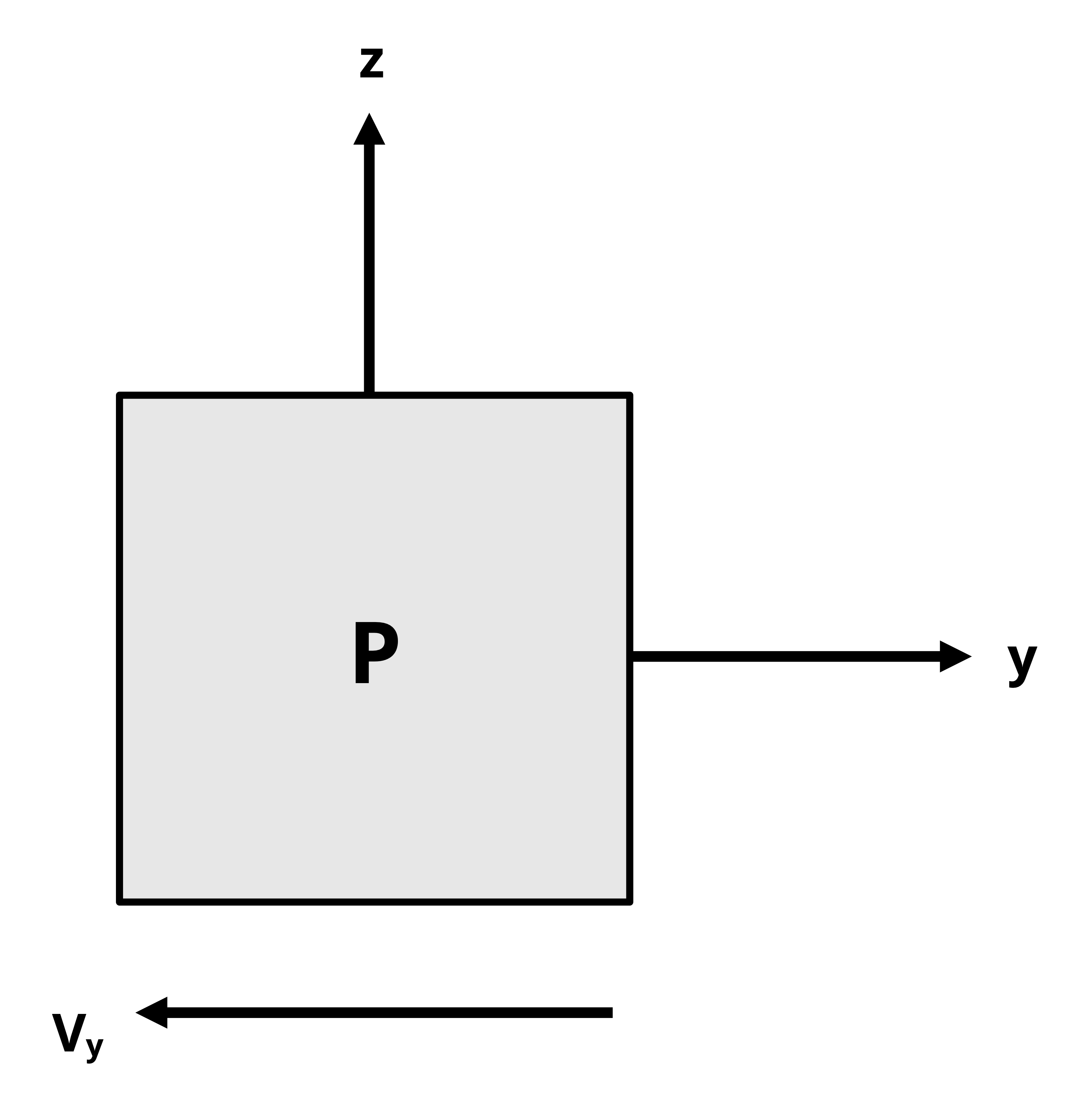

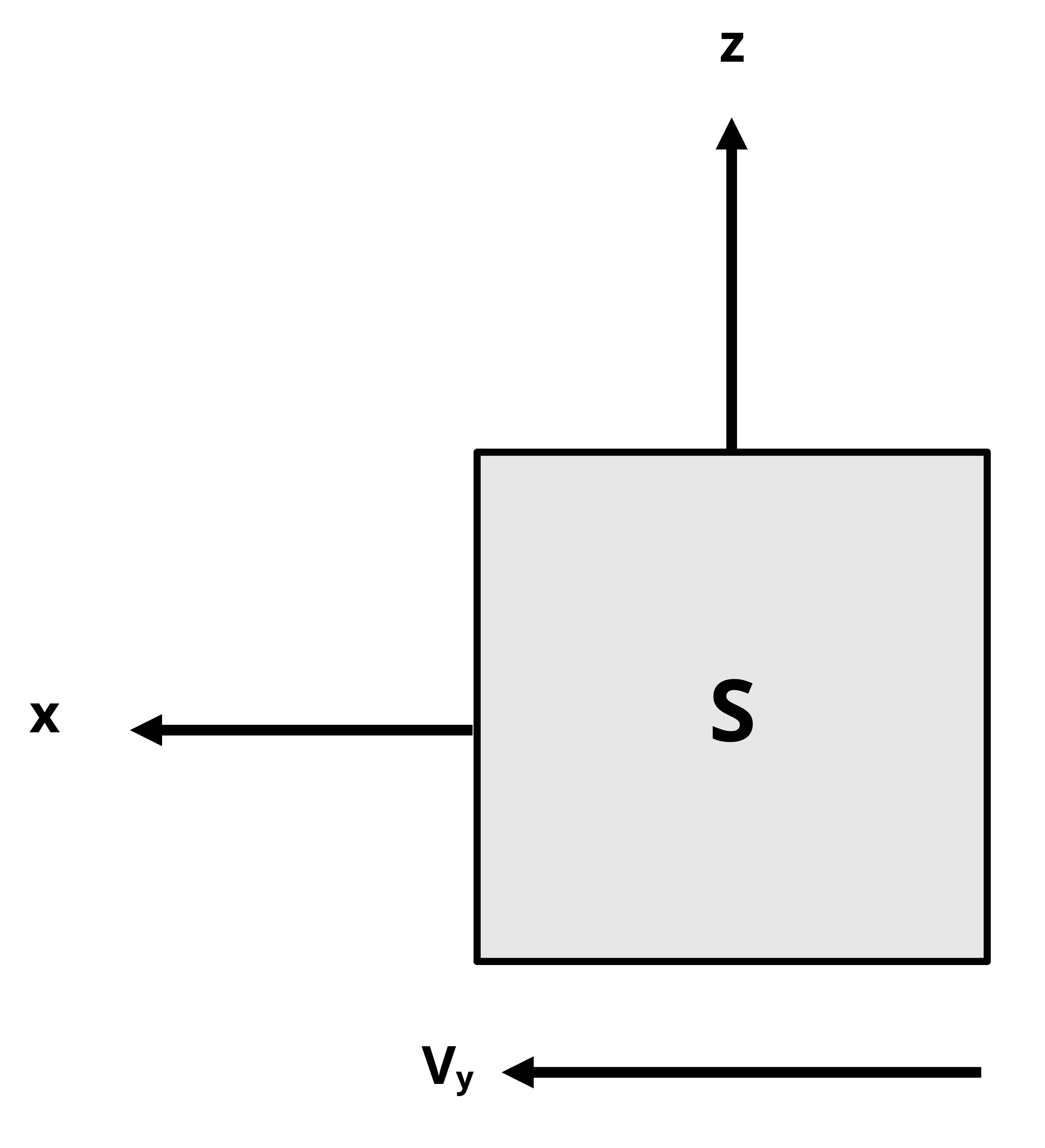

These directions could change from point to point depending on the location of the point of interest and the geometry of the body. For example, consider the structure in Figure 14.2 with the x-, y-, z-axes oriented at the origin as shown. To examine point P on the structure, we make a vertical cut at point P. The direction normal to the cut surface is the x direction, so the x-axis is the longitudinal axis. When viewing the cut surface looking down the x-axis, you see the y-axis and z-axis on the cross-section, so those are the cross-sectional axes. In this view, the y-axis appears to be the vertical (V) axis of the cross-section and the z-axis is horizontal (H).

In contrast, for point Q we must make a horizontal cut to examine that point. The normal direction to the cut is then the vertical, or y-axis, and the cross-sectional axes as viewed looking down the y-axis are the x-axis and z-axis. In this view, the x-axis would appear to be the horizontal axis of the cross-section and the z-axis would appear to the vertical axis of the cross-section.

Depending on your perspective, you may switch the cross-sectional axes you consider to be horizontal versus vertical. Ultimately this will not matter as long as you correctly distinguish between the longitudinal and cross-sectional directions.

In the following sections we will express equations in terms of these generic directions so that they will apply to any orientation of coordinate axes.

14.2 Combined Normal Stress

Click to expand

Previous chapters considered individual sources of longitudinal normal stress: axial loads (Chapter 5), bending loads (Chapter 9), and pressure loads (Chapter 13). With all three of these forms of loading present we can express the generalized equation for total longitudinal stress as

\[ \sigma_L =\frac{\sum F_L}{A}+\sigma_{bending}+\frac{p r}{2 t}\text{ ,} \]

𝜎L = Total normal stress in the longitudinal direction [Pa, psi]

FL = Force in the longitudinal direction [N, lb]

A = Cross-sectional area [m2, in.2]

𝜎bending = Bending stress (discussed in more detail below) [Pa, psi]

p = Internal pressure [Pa, psi]

r = Inner radius of pipe or pressure vessel [m, in.]

t = Wall thickness of pipe or pressure vessel [m, in.]

If there is pressure loading in addition to the contribution to the longitudinal normal stress indicated above, there will also be normal stress in the cross-sectional directions equal to the hoop stress.

\[\sigma_V=\sigma_H=\sigma_{hoop}=\frac{pr} {t}\]

Of course, for problems without pressure, the pressure terms would be excluded.

Of the three types of longitudinal normal stress, bending stress tends to be the most complex to understand in terms of calculation inputs and signs, especially with varying coordinate axes directions. Section 14.2.1 revisits the concept of bending stress to discuss how to generalize the Chapter 9 equations to any orientation of body with any arrangement of coordinate axes.

14.2.1 Generalized Bending Stress Equation

Section 9.3 derived an equation for bending stress in the x direction based on bending around the cross-sectional axes y and z. That equation is

\[ \sigma_x=-\frac{M_z y}{I_z}+\frac{M_y z}{I_y} \]

The minus sign in front of the Mz term and the plus sign in front of the My term are part of the derived equation. When the correct signs for Mz, My, y, and z are inserted, the correct sign of the stress is obtained (positive for tensile and negative for compressive). Note that Chapter 9 considered no other cross-sectional axes so that focus on the general concept of bending stress could be more easily maintained.

When the cross-sectional axes are not y and z, we apply the same general form of the above bending stress equation. However, for a different set of axes, we not only need to change the bending moment and second moment of area axes in the equation but also need to reconsider the signs in front of each term. In any given bending load situation the bending moments are the moments around the centroidal axes of the cross-section (V and H) and the resulting normal stress is in the longitudinal direction (L).

Given this information, we can then reframe the bending stress equation in a generalized form.

\[ \boxed{{\sigma_{(bending)}= \pm\left|\frac{M_V\ d_H}{I_V}\right| \pm\left|\frac{M_H\ d_V}{I_H}\right|}}\text{ ,} \tag{14.1}\]

𝜎(bending) = Bending stress in the longitudinal direction [Pa, psi]

MV = Bending moment around the vertical axis of the cross-section [N⸱m, lb⸱in.]

MH = Bending moment around the horizontal axis of the cross-section [N⸱m, lb⸱in.]

dH = Horizontal distance between the point of interest on the cross-section and the V-axis [m, in.]

dV = Vertical distance between the point of interest on the cross-section and the H-axis [m, in.]

IV = Second moment of area about the vertical axis of the cross-section [m4, in.4]

IH = Second moment of area about the horizontal axis of the cross-section [m4, in.4]

Figure 14.3 illustrates the distances dH and dV for the case where the stress at the example point P on the cross-section is being calculated.

The absolute values used for the bending stress terms with the ± in front indicate that we will calculate the magnitude of each bending stress term and then assess the signs of the terms independently. We assess the signs by visualizing the bending direction or by using visualization tools, described below. Recall that compressive stresses are considered negative and tensile stresses are positive.

Also helpful to note is that MH does not affect the normal stress of points directly on the H-axis and MV does not affect the normal stress of points directly on the V-axis. This is evident from the fact that dH = 0 for a point on the V-axis and dV = 0 for a point on the H-axis.

14.2.2 Assessing Bending Stress Signs for Generalized Bending Stress Equation

The sign on each of the two bending stress terms in Equation 14.1 is determined by inspection of the bending direction. Section 9.1, showed that a bending moment around the horizontal axis causes the normal stress to vary along the vertical axis of the cross-section. Section 9.3 showed that a bending moment around the vertical axis causes normal stress to vary across the cross-section’s horizontal axis. Which side is in tension versus compression in each case depends on the direction (clockwise versus counterclockwise) of the bending moment as well as the location of the point on the body.

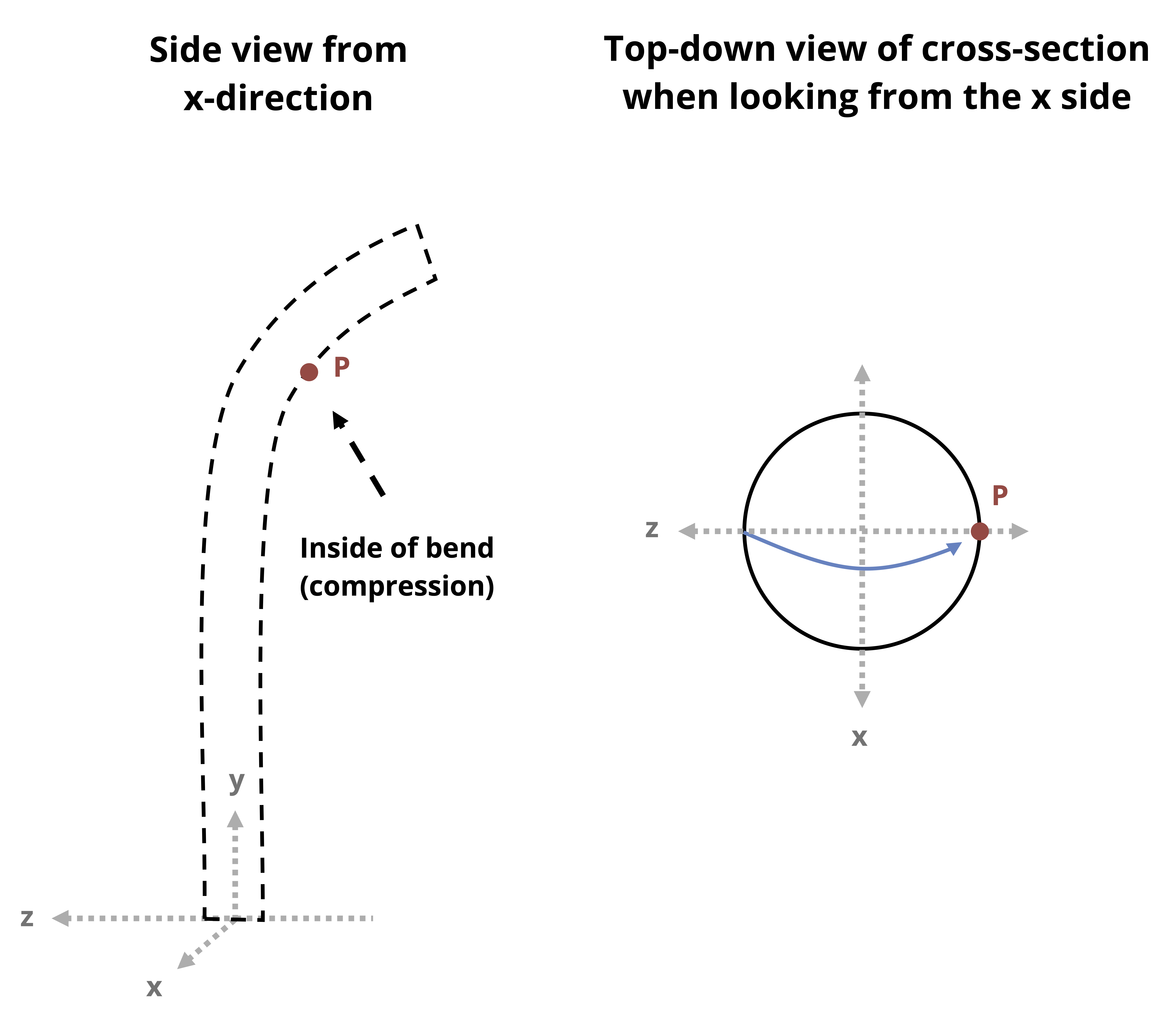

If we can visualize the expected bending direction due to loading, we can assess whether a point will be on the “inside” of the bend (compression) or on the “outside” of the bend (tension). For example, in Figure 14.4 the rightward horizontal force results in bending around the V-axis of the cross-section. The direction of the bending is such that all points to the right of the V-axis on the cross-section are on the inside of the bend (compression) and all points to the left of the V-axis on the cross-section are on the outside of the bend (tension).

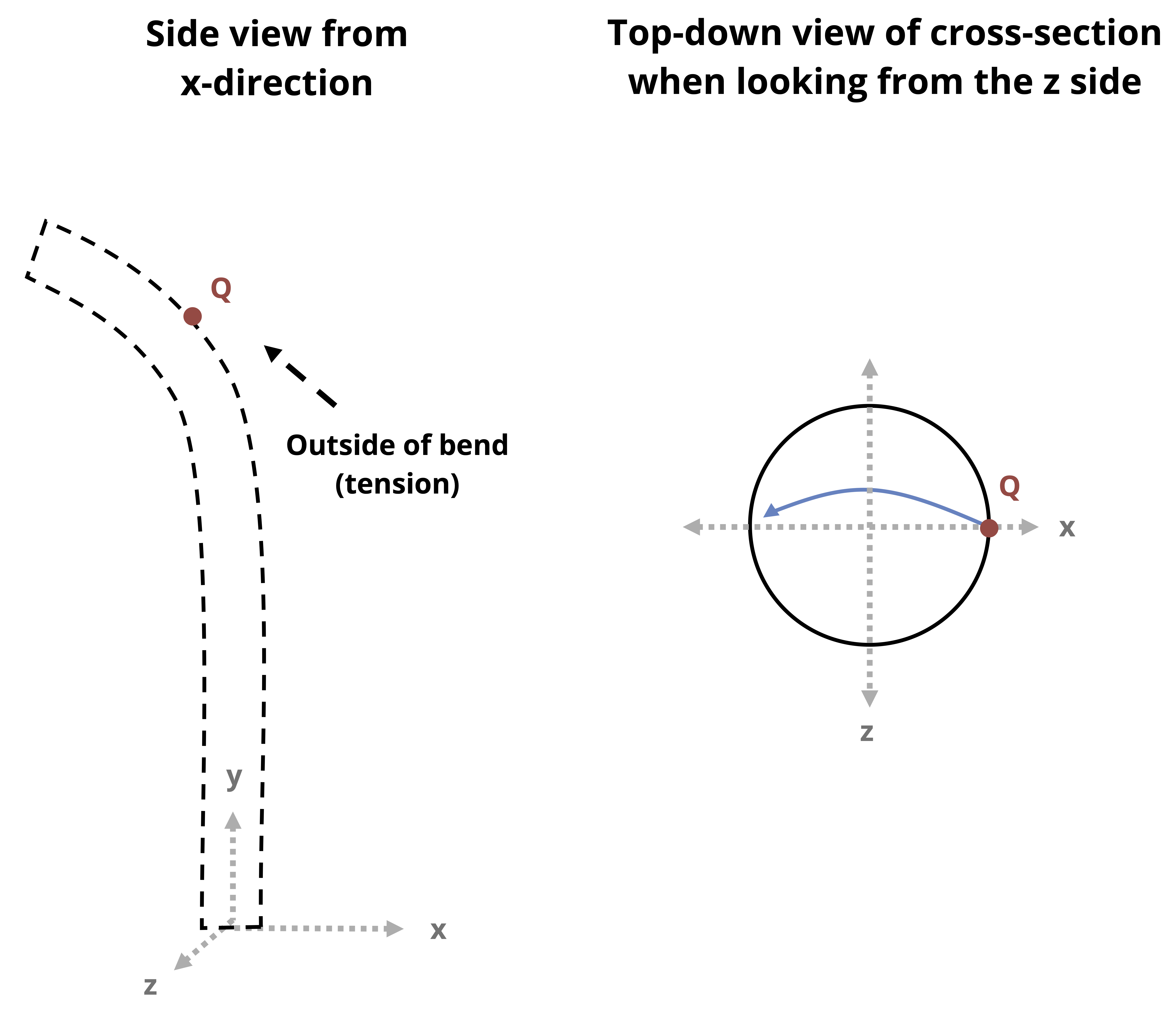

In Figure 14.5, the force in the V direction results in a bending moment around the H-axis. The direction of the bending is such that all points above the H-axis on the cross-section are on the inside of the bend (compression) and all points below the H-axis on the cross-section are on the outside of the bend (tension).

If visualization is difficult, use the following tool (refer to Figure 14.6):

- Draw the cross-section as viewed from the free end or cut end toward the origin. For example, in the case of the columns in Figure 14.4 and Figure 14.5, we would draw the top-down view of the cross-section.

- Draw the bending moment arrows around the V-axis and H-axis on the sketch of the cross-section. Exaggerate the arrows so they are drawn all the way across.

- Make sure to draw the bending moment arrows such that they cross over (or in front of) the bending axis (as opposed to under or behind).

- The side the arrowhead points to is the compressive side, and the side the tail of the arrow is on is the tensile side.

This approach is demonstrated for the bending stress calculation in Example 14.1.

14.2.3 Eccentric Loading

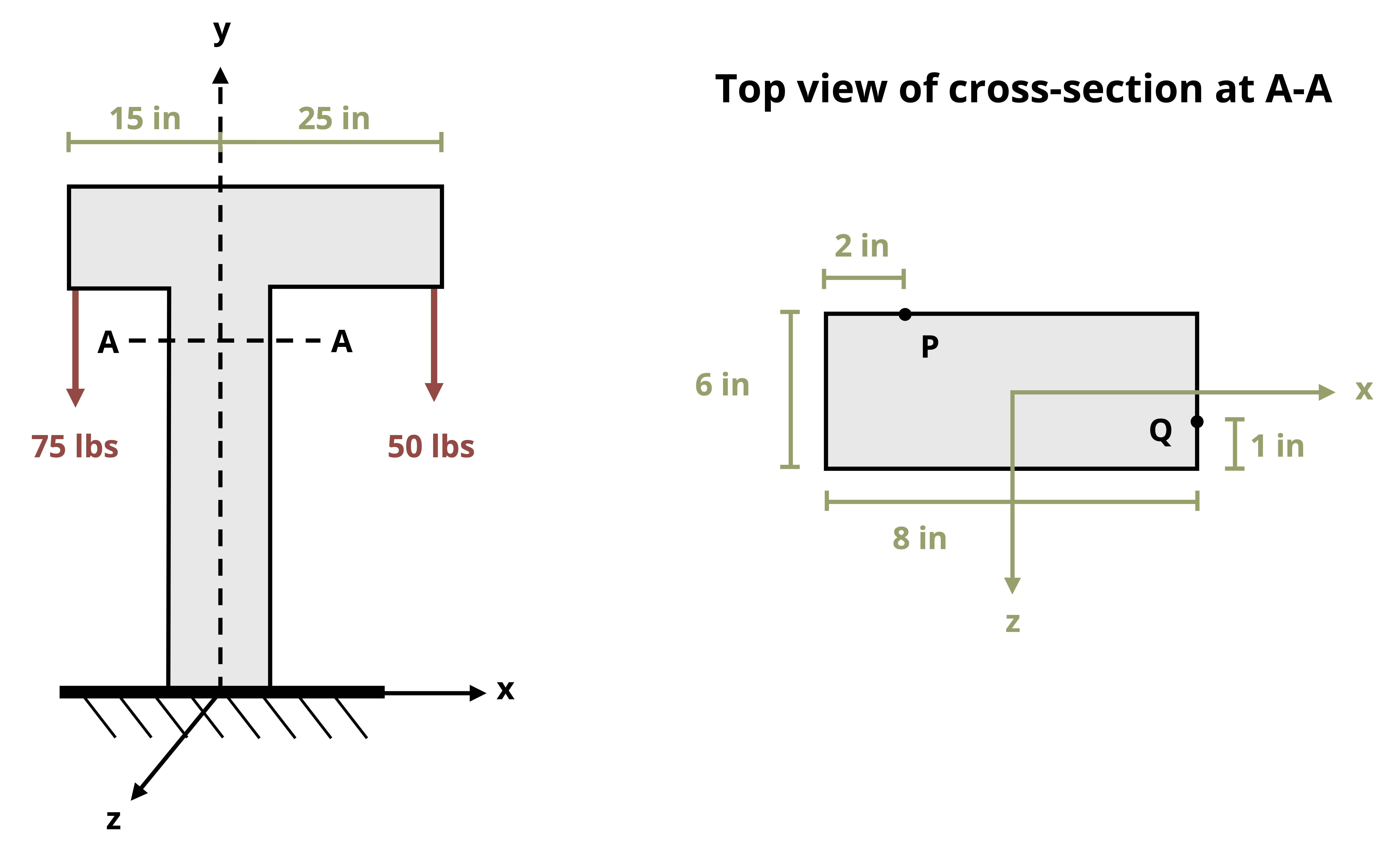

When the line of action of an axial load doesn’t pass through the centroid of a cross-section, it results in both a normal reaction force and a bending moment. For example, consider the traffic light and corresponding FBD shown in Figure 14.7.

The vertical support pole is subjected to normal forces from the weights of the traffic lights (the weight of the horizontal poles, cameras, etc. are assumed to be negligible for this example). Also, bending moments around both cross-sectional axes (x and z) result from the weights not being directly centered on the support pole.

The total normal stress in the longitudinal direction, σL, at any given point on the pole would be given by

\[ \sigma_L =\frac{\sum F_L}{A}+\sigma_{bending} \]

In terms of the general axes discussed in Section 14.1, and substituting in Equation 14.1 for the bending stress, we have

\[ \boxed{{\sigma_L= \pm\left|\frac{F_L}{A}\right| \pm\left|\frac{M_V\ d_H}{I_V}\right| \pm\left|\frac{M_H\ d_V}{I_H}\right|}}\text{ ,} \tag{14.2}\]

𝜎𝐿 = Bending stress in the longitudinal direction [Pa, psi]

FL = Internal normal force in the longitudinal direction [N, lb]

A = Cross-sectional area [m2, in.2]

MV = Bending moment around the vertical axis of the cross-section [N⸱m, lb⸱in.]

MH = Bending moment around the horizontal axis of the cross-section [N⸱m, lb⸱in.]

dH = Horizontal distance between the point of interest on the cross-section and the V-axis [m, in.]

dV = Vertical distance between the point of interest on the cross-section and the H-axis [m, in.]

IV = Second moment of area about the vertical axis of the cross-section [m4, in.4]

IH = Second moment of area about the horizontal axis of the cross-section [m4, in.4]

The sign for the first term is positive if the FL is tensile (directed away from the cross-section) and negative if FLis compressive (pointed toward the cross-section).

Example 14.2 and Example 14.3 demonstrate the calculation of normal stress in eccentric loading problems.

Example 14.4 demonstrates a loading that includes pressure as part of the loading combination and drawing the resulting stress element.

14.3 General Shear Stress

Click to expand

Shear stress due to torsion was discussed in Chapter 6 while shear stress due to transverse loading was discussed in Chapter 10. This section discusses the additional considerations that go into determining the total shear stress when both forms of loading are present.

14.3.1 Shear Stress Due to Torsion

As discussed in Section 6.1, shear stress due to torsion in a circular shaft can be calculated as Equation 6.1.

\[ \tau_{(torsional)}=\pm\left|\frac{T \rho}{J}\right|\text{ ,} \]

\(T=Torque=\sum M_L\) [N·m, lb·in.]

𝜌 = Radial distance from center to the point of interest on the cross-section [m, in.]

J = Polar second moment of area for circular cross-section [m4, in.4]

Once again, as was done for the normal stress equations, the ± and absolute value is used to signify that we will calculate the magnitude of the stress and assess the sign independently.

General problems may require us to sum moments to calculate T, so it’s important to remember that torque is the moment about a body’s longitudinal axis or that moment component causes the body to twist. Since this form of shear stress is combined with transverse shear stress to obtain the total stress, we must understand the sign of the shear stress.

Section 12.1 showed that the sign of shear stress depends on the orientation of the shear stress arrows on the stress element that represents the stress state of the point of interest. To determine in which direction to draw a shear stress arrow on a stress element for a particular point, cut the body at one edge of the stress element and visualize the direction in which the shear load would act across the cut.

For example, Figure 14.8 shows the stress element to be in the L-H plane. When the cylinder is cut at the top of the stress element, examine the bottom section of the cylinder and note that the reaction torque at the cut surface should be opposite in direction to that applied at the bottom surface. This results in a counterclockwise (from the top view perspective) reaction torque at the cut, which means the top section tends to want to twist (and exert a force) from left to right across the stress element’s top edge.

If the longitudinal axis is positive upward, the top face of the element is a positive L face. In addition, if the horizontal axis is positive to the right, the rightward shear force arrow acts in the positive H direction. A positive H force on the positive L face constitutes a positive shear stress.

Similarly, when the cut is made at the bottom edge of the element, we can examine the cylinder’s top section, for which equilibrium dictates there is a clockwise (again, based on top view) reaction moment at the cut edge. This means that the bottom section tends to want to twist from right to left across the bottom element’s edge. The right to left arrow on the bottom face of the element represents a negative H force on a negative L face. The double negative indicates a positive shear stress, confirming the result obtained above from studying the bottom section of the cylinder.

If the H-axis were to be oriented to be positive to the left instead, then this same shear stress would be negative. The same can be said if the H-axis is positive to the right but the L-axis is positive downward.

14.3.2 Shear Stress Due to Transverse Shear Force

In Chapter 10 the equation \(\tau=\frac{V Q}{I t}\) (Equation 10.2) was evaluated to find the shear stress due to a transverse shear force V that arises from a nonconstant bending moment. In that chapter only one direction of shear force was considered for each problem and the sign of the shear stress was not evaluated.

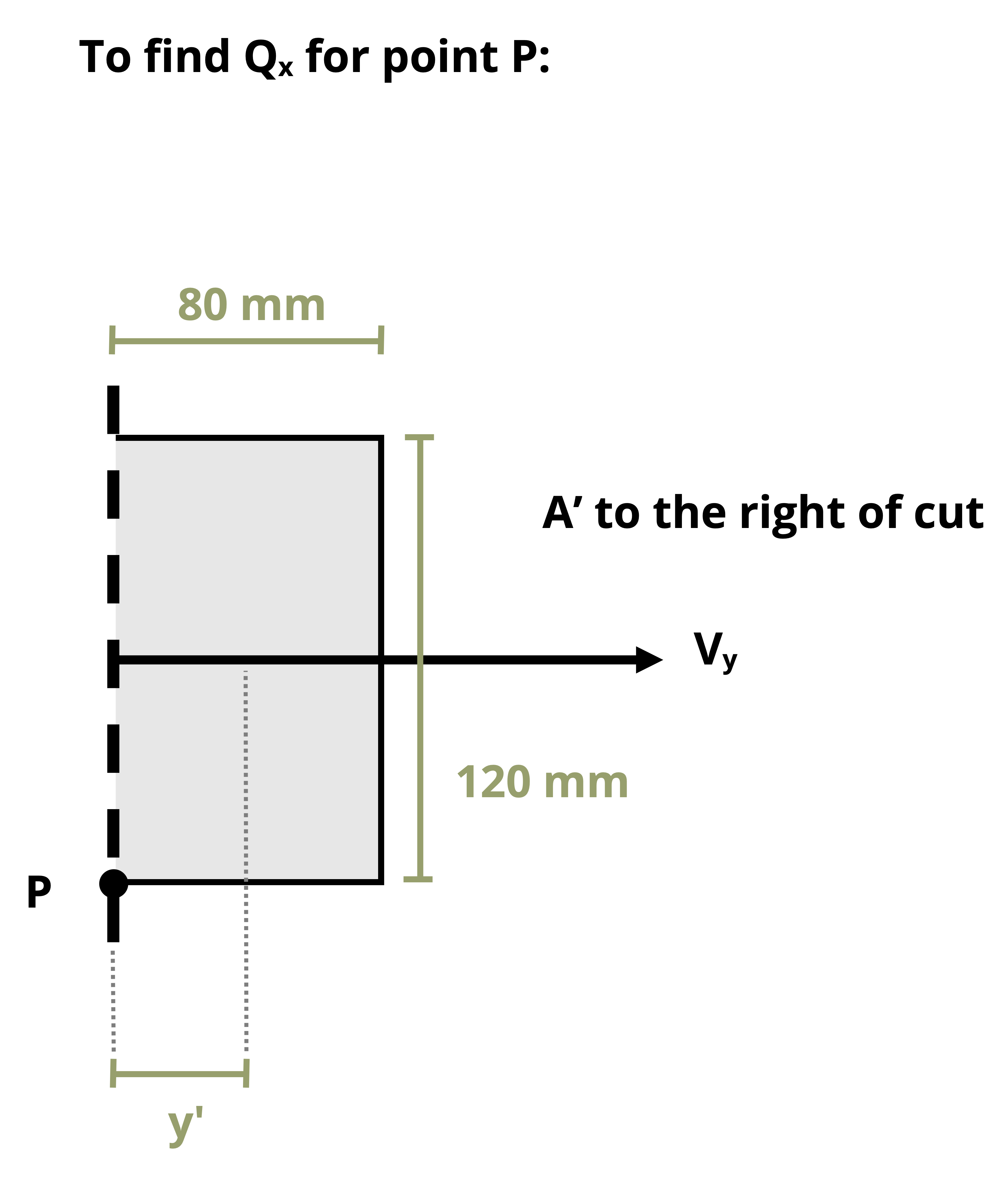

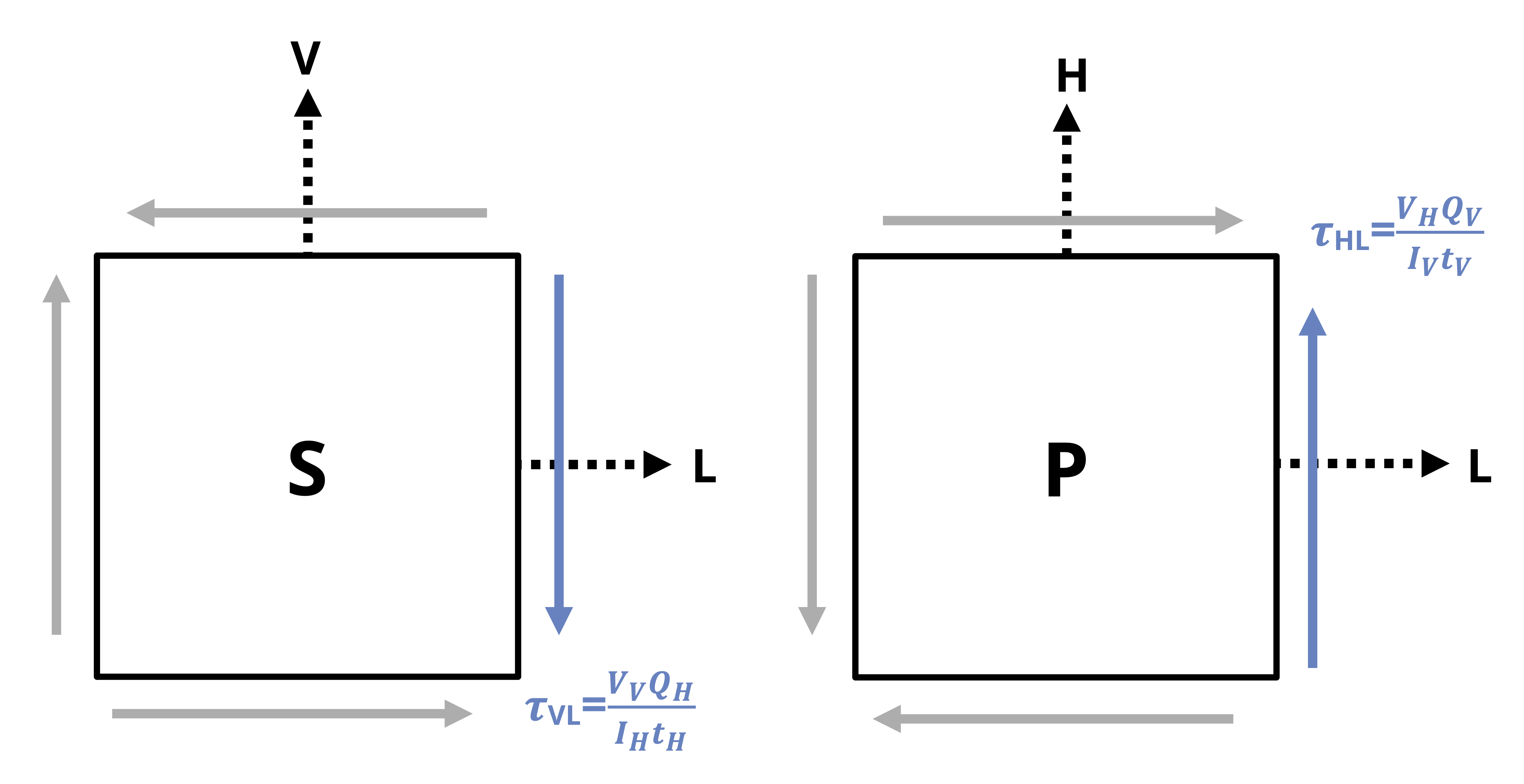

For general loading we may have two directions of transverse shear force corresponding to the two cross-sectional axes directions, as shown on the illustration of the bar in Figure 14.9. In this case, we will need to apply the transverse shear stress equation for both directions and also understand the signs so that we can combine them with each other and with the torsional shear stress. The direction of the shear force will affect the direction of the cut made across the cross-section to find Q, t, and the axis the second moment of area is based on.

When applying the transverse shear stress equations for specific directions of shear force, keep the following in mind:

- The cut on the cross-section to determine the first moment of area Q will be perpendicular to the direction of shear force direction (illustrated on the cross-sections in Figure 14.9).

- The second moment of area (I) will be based on the axis perpendicular to the shear force direction.

- The thickness (t), refers to the thickness of the solid part of the cross-section that is cut through to calculate Q (illustrated on the cross-sections in Figure 14.9).

Using the same reference axes as in the general normal stress equation—H for horizontal cross-sectional axis and V for vertical cross-sectional axis—the transverse shear stress equation can be written as follows:

\[ \boxed{{\tau_{(transverse)}= \pm\left|\frac{V_H Q_V}{I_V t_V}\right| \pm\left|\frac{V_V Q_H}{I_H t_H}\right|}}\text{ ,} \tag{14.3}\]

𝜏(transverse) = Transverse shear stress at point of interest [Pa, psi]

VH = Internal horizontal shear force [N, lb]

VV = Internal vertical shear force [N, lb]

QV = First moment of area about the vertical axis passing through the point of interest [m3, in.3]

QH = First moment of area about the horizontal axis passing through the point of interest [m3, in.3]

IV = Second moment of area about the vertical centroidal axis of the cross-section [m4, in.4]

IH = Second moment of area about the horizontal centroidal axis of the cross-section [m4, in.4]

tV = Vertical thickness of the cross-section cut through [m, in.]

tH = Horizontal thickness of the cross-section cut through [m, in.]

When assessing the contributions to shear stress present for any given point, consider these simplifying observations:

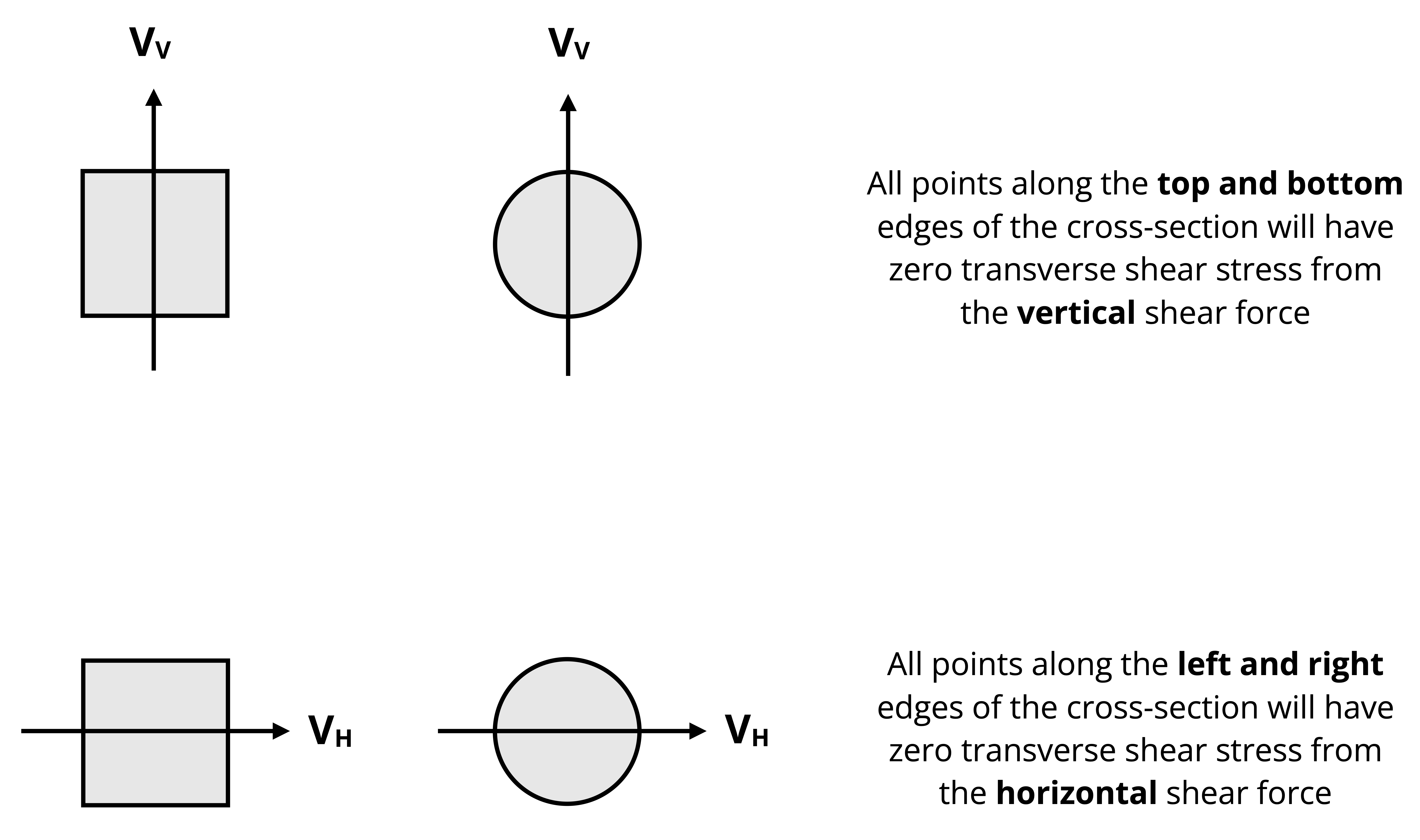

If a point is on the top or bottom edge of a noncircular cross-section or is the top or bottom point of a circular cross-section, it will experience no transverse shear stress from a vertical shear force.

If a point is on the left or right edge of a noncircular cross-section or is the leftmost or rightmost point of a circular cross-section, it will feel no transverse shear stress from a horizontal shear force.

For example, in Figure 14.9, point P will experience no shear stress from VV and point S will feel no shear stress from VH. Figure 14.10 further illustrates the preceding statements.

The reason is that in the case of a vertical shear force bending is around the H-axis so the top and bottom edges of the cross-section are free edges. Similarly, in the case of a horizontal shear force bending is around the V-axis so the left and right edges of the cross-section are free surfaces. For a circular cross-section the idea is similar but applies only to the points at the top/bottom and left/right positions along the centroidal axes on the perimeter. In other words, Q = 0 for the top and bottom edges in the case of a vertical shear force and for the left and right edges for a horizontal shear force.

The signs on the shear stress are determined as described in Section 14.3.1 for torsion. The direction of the internal shear force is determined by cutting the body at the point of interest, drawing the FBD of the cut section, and applying equilibrium. The resulting shear stress is considered to act in that same direction on the cut surface of the element. For example, in Figure 14.9, point S is on the V-L plane. Figure 14.11 shows the element drawn from the side view, looking down the H-axis. The shear force VV acts downward on the stress element’s right side. With the axes are oriented such that the longitudinal axis is positive to the right, the right side of the stress element is the +L-face. If the V-axis of the element is positive upward, then VV is acting in the negative V direction on the +L-face, indicating a negative shear stress. Similarly, point P is on the H-L plane. In Figure 14.11 the stress element is drawn from the top view (viewing down the V-axis). The shear force VH acts upward on the stress element’s right side. If the right side is the +L-face and the H-axis is positive upward, then VH acts in the +H direction on the +L-face, indicating a positive shear stress.

14.3.3 Combined Shear Stress

Now we can consider the case of bodies simultaneously subjected to both torsion and transverse shear stresses. Given a general loading situation, we may need to calculate the torque and also identify which of the forces constitute transverse shear forces. It will be helpful to remember:

The transverse shear forces are the internal forces in the directions of the cross-sectional axes.

Torque is the internal moment about the longitudinal axis.

- Also recall that torsion is only considered for circular cross-sections.

The total shear stress acts in the plane of the point of interest. It can be calculated as

\[ \boxed{{\tau= \pm\left|\frac{T \rho}{J}\right| \pm\left|\frac{V_H Q_V}{I_V t_V}\right| \pm\left|\frac{V_V Q_H}{I_H t_H}\right|}}\text{ ,} \tag{14.4}\]

𝜏 = Shear stress at point of interest [Pa, psi]

T = Internal torque [N·m, lb·in.]

𝜌 = Radial distance from centroid to point of interest [m, in.]

J = Polar second moment of area [m4, in.4]

VH = Internal horizontal shear force [N, lb]

VV = Internal vertical shear force [N, lb]

QV = First moment of area about the vertical axis passing through the point of interest [m3, in.3]

QH = First moment of area about the horizontal axis passing through the point of interest [m3, in.3]

IV = Second moment of area about the vertical centroidal axis of the cross-section [m4, in.4]

IH = Second moment of area about the horizontal centroidal axis of the cross-section [m4, in.4]

tV = Vertical thickness of the cross-section at the cut made for QV [m, in.]

tH = Horizontal thickness of the cross-section at the cut made for QH [m, in.]

Example 14.5 demonstrates the calculation of total shear stress when both torsion and transverse shear are acting.

Example 14.6 demonstrates the calculation of transverse shear stress with multiple directions of shear force.

14.4 General Combined Stress

Click to expand

Once the total normal stress and total shear stress at a specified point are calculated, the general stress state can be represented on a stress element and used to determine principal stresses, principal planes, and max/min shear stresses.

Example 14.7 extends the problem from Example 14.6 to find the principal stresses and max/min shear stresses.

Summary

Click to expand

References

Click to expand

Figures

All figures in this chapter were created by Kindred Grey in 2025 and released under a CC BY license.